Temperament Testing: From Tiny Paws to Trusting Pets

An in-depth look at our step-by-step temperament testing process that ensures every rat we adopt out is confident, people-friendly, and matched perfectly to their future home.

Inside Our Rattery’s Temperament Testing

Imagine a three-week-old rat pup venturing outside its nest for the very first time. Its eyes have only recently opened, and every sight, sound, and smell is brand new. I gently scoop up the little one and place it into a large cement mixing tub lined with fresh pine shavings in my living room. This tub is completely unfamiliar territory – intentionally so. The pup sniffs the air, whiskers twitching, unsure what to expect. This is the beginning of our temperament testing journey, a careful process we undertake with every litter to ensure we raise not just healthy rats, but confident, friendly companions and exceptional breeding candidates. In this detailed look behind the scenes, I will walk you through how we conduct temperament tests at 3 and 5 weeks of age, why each step matters, and how it all leads to perfect pet rats and the next generation of gentle breeders.

Why Temperament Testing Matters

Perfect pet rats aren’t just about cute colors and markings. Rats bred thoughtfully for companionship start with temperament instead of just looks. A rat’s personality will determine whether it curls up for cuddles, eagerly explores new toys, or panics at a sudden noise. We want our rats to thrive in their new homes and form loving bonds with their humans. That’s why temperament is our top priority (right alongside health). Through years of experience (and a bit of heartbreak), we’ve learned that simply handling babies a lot from birth isn’t enough. In fact, it can sometimes mask underlying temperament issues. Studies and breeders estimate that genetics account for roughly 50% (or more) of a rat’s temperament, with the rest influenced by socialization. Early over-handling can produce pups that seem tame in our care, but if that handling stops for a few days, or the rat becomes distressed, their true genetic disposition may surface. A formerly “sweet” baby might suddenly become skittish or even nippy. This is what breeders refer to as “temperament masking.”

“Why not just cuddle them constantly from day one?” We intentionally hold off on heavy socialization until after 5 weeks old for this very reason. By minimizing handling in the first few weeks (aside from quick health checks and cage cleanings), we allow each rat’s natural, inherited personality to shine through. This way, when we do begin formal testing around 3 weeks, we’re seeing the pup’s true baseline behavior, not just a reaction to being accustomed to hands. It might sound unusual to delay snuggles (it’s so tempting to scoop up those babies), but this approach yields far more stable and reliable temperaments in the long run. We’re essentially stress testing their genetics: only those with solid, inborn good temperament will pass our evaluations and move on to lots of socialization.

By investing this time and care, we dramatically lower the risk of adopting out a fearful or aggressive rat. Our adopters get peace of mind that their new pet’s friendliness isn’t a fluke of intensive handling, it’s in their nature. Now, let’s step through how these tests work, almost as if you were right here with us, peeking over my shoulder in the rattery.

The 3 Week Old Evaluation

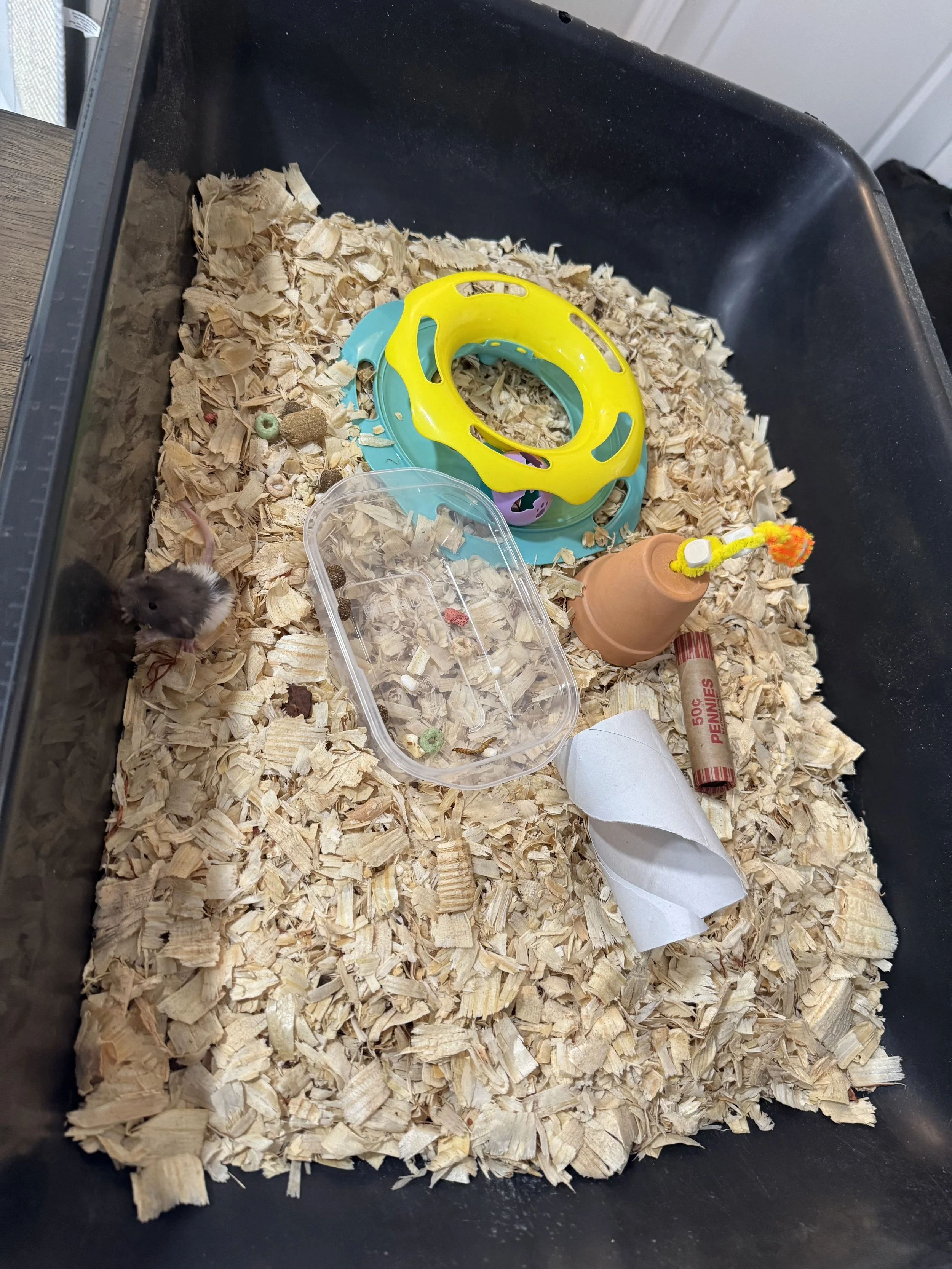

Between 2½ and 3 weeks of age, baby rats hit a milestone: they become mobile, curious, and start nibbling solid food. This is when we perform the first formal temperament test. The entire litter is brought outside of the rattery room into a new space (often my living room or dining room). The change of scenery is important, because it ensures the pups aren’t just behaving confidently due to familiarity with their cage. Instead, we see their reactions to a 100% new environment. I use a roomy, high-sided cement mixing tub with clean bedding as our testing arena. Pups can’t climb out, and it’s neutral ground with no lingering smells of mom or home cage.

One by one, I gently evaluate each pup on a variety of handling and interaction points, taking careful notes on a printed 3-Week Temperament Test form. Here’s what a typical session looks like:

Initial Handling & Petting

The Process:

I reach into the tub and lift the pup into my hands. At this age they’re tiny, fitting easily in my palm. I stroke the baby along its back and sides, simulating how a human might pet them. How do they react? Some pups completely relax, melting into my hand as I rub their shoulders. They might even close their eyes or brux (grind teeth softly) in contentment, a wonderful sign that they’re comfortable with human touch. Others are mostly relaxed but squirm just a little, perhaps an instinctual wiggle before they settle down. A mild protest at this age is okay; they’re still getting used to being handled. We note those as “squirms a bit.” Then there are pups who struggle at first but then relax after a few seconds, they’re unsure initially, but they can accept handling with a bit of patience. This is also a reasonably good response; they might just need more confidence.

Once in a while, a pup will freeze up, stiff as a board. You can feel their little body go tense, and they might stare wide-eyed or breathe fast. Freezing in fear is a red flag, it tells me this baby is very uncomfortable being touched right now. Equally concerning are those who actively resist being petted, they twist, turn, and try to get away from my hand. The most extreme reaction is what I call the “suicide jump.” A pup that fully panics will launch itself out of my hands with no regard for safety, desperate to flee. It’s a scary behavior (for both of us!) and a strong indicator of poor temperament. Pups that completely resist handling or try to leap away are marked as failing this portion. This level of terror or frantic escape behavior at such a young age suggests a high-strung, fearful nature that would make them unhappy pets and risky to place in anyone’s home.

Why it Matters:

A rat that enjoys being held and pet, or at least tolerates it calmly, is likely to be a cuddly, affectionate companion. One that fights your touch or tries to flee, on the other hand, is signaling that human contact deeply stresses them. By identifying that now, we can avoid placing a traumatized or highly fearful rat into a pet home. It’s better for the rat and the adopter; no one wants a pet that is terrified of them. This test lays the foundation: we’re looking for inherent trust or at least tolerance of handling.

The Flip Test

The Process:

Next, I carefully roll the pup onto its back in the cradle of my hands. Rats are naturally most vulnerable on their backs, this position is like saying “I trust you not to hurt me.” I support the baby’s body while it’s belly-up and observe. Does the pup relax or resist? A positive sign is when a pup wiggles for a moment and then settles down, allowing me to hold them upside-down without protest. Some will even fully relax in this position, feet drooping and body loose, that’s an excellent indicator of trust. If a pup struggles briefly but then finds a bit of calm, I note that too (“wiggled then relaxed”).

However, a few things can happen that show a pup isn’t comfortable. One is if the body goes completely stiff, little legs sticking out rigidly, tail straight, like a tiny statue. That stiffness signals fear, the pup is essentially freezing. Another clear sign of discomfort is if the baby opens its mouth when flipped. I’ve seen nervous pups do a big yawn-like mouth gape or even bare their teeth for a second, it’s a dramatic “I don’t like this!” statement. Occasionally a pup might let out a tiny squeak of protest while being held on its back. Squeaking is rare at this age unless they’re quite upset or frightened. Any combination of open mouth, squeaking, or stiff body during the flip test gets a negative mark. Lastly, if a pup immediately writhes and tries to right itself or escape every time (never relaxing even for a moment), that’s noted as well, they’re unwilling to be in a vulnerable position at all.

Why it Matters:

The flip test checks for submission and trust. A rat that can relax on its back is likely to be more accepting of necessary handling (like health exams, gentle nail trims, or a child cradling them). A rat that cannot stand being upside-down, to the point of fear or aggression, may have issues with dominance or anxiety. In a social species like rats, a pup that refuses to ever submit (even when we’re as gentle as possible) might become a domineering adult or one that reacts poorly if forced into any restraint. We want to catch any extreme reaction now. Many well-tempered rats might not love being on their backs (few do), but they should recover quickly from the surprise and not feel the need to bite or panic. Think of it like a trust fall, the ones who pass realize we won’t hurt them, and they “fall” calmly into our hands.

The Dominance Test

The Process:

This is an extension of the flip test. While the pup is on its back, I place two fingers gently on its chest, applying light pressure to simulate another rat or a human holding it down. In rat social behavior, dominant rats will pin submissive ones on their back in play or squabbles, a submissive rat will stop squirming as a sign of yielding. I want to see if the pup will “give in” to gentle restraint or continue to thrash. So, when I pin them for a moment, I observe: do they squirm a little and then submit, relaxing under my fingers? That would be ideal, it shows they aren’t hyper-dominant and can accept being physically controlled briefly. Some pups indeed stop resisting and lie there, which earns them a note of “fully submit”. Other pups might squirm a lot at first, pushing against my fingers, little legs cycling, but then finally sigh and still themselves (“squirm then submit”). That’s also an okay result; they protest but ultimately relent, which is what we hope to see.

If a pup keeps fighting furiously the entire time or starts squeaking and squirming in panic, that’s a bad sign. A consistent unwillingness to submit, essentially “you can’t hold me, let me go!”, could mean this rat will be very difficult to handle as it grows (imagine trying to hold a wiggly, determined adult that never stops struggling). It can also hint at a very dominant personality, such a rat might later bully cage-mates or challenge humans (for example, nipping when being restrained). We mark heavy resistance or squeaking during the pin test as a negative mark for this portion.

Why it Matters:

This test helps predict the rat’s social dominance level and tolerance for restraint. Rats that readily submit when held down tend to be more easygoing, both with people and other rats. Those that absolutely refuse may end up being the “bossy boots” of their litter or may never quite enjoy being held in certain ways. Knowing this allows us to plan future cage group dynamics (for instance, not putting two highly dominant rats together in a new home) and to decide if a rat is suitable as a pet at all. Extremely unyielding or distressed individuals at this age raise concerns that they could exhibit defensive aggression when older. Our goal is to avoid placing any rat that might later become a biter or perpetual struggler in a home, where it could frustrate the owner or end up returned.

The Scruff Test

The Process:

Next up is a quick check that often surprises people unfamiliar with breeding: I gently scruff the pup, lifting it for just a second by the loose skin on the back of its neck and shoulders (just like a mother rat might carry a baby). Scruffing must be done carefully and only on loose skin, at 3 weeks, most pups have a good bit of “scruff” to grab. I’m not dangling them harshly or for longer than a couple of seconds, just quickly seeing their reaction to this form of restraint. A perfectly even-tempered pup will often tuck its hind feet up and remain relaxed while scruffed, essentially going limp, calm and still. This looks a bit like a kitten being scruffed, they just sort of hang there peacefully. That’s the best outcome and earns a top score. Other pups might let their feet dangle but still stay mostly relaxed, also a good sign. Some may struggle for a second or two and then stop, realizing it’s not hurting them (that’s “struggles then relaxes”). I consider that a pass as well; they had an instinct to resist but quickly figured out there was no danger.

If a pup starts to thrash and keeps fighting being scruffed, or can’t be properly scruffed at all because it’s contorting so much, that’s a negative mark (“resists scruffing”). A bit of squirming is okay, but vigorous squirming, squeaking, or trying to twist out of the hold indicates high stress or defensiveness. We also have an option on the form “hard to scruff, results may be inaccurate” – this is used if the pup’s body type makes scruffing tricky (for example, a hairless or very wiggly one with not much skin to grab). In those cases I might rely more on the other tests to judge them.

Why it Matters:

At some point, most pet rats will need to be restrained for a moment, whether for a health check, trimming nails, administering medicine, or being moved between enclosures. A rat that accepts scruffing or gentle restraint without terror is much easier (and safer) to work with. We’re looking for an innate lack of aggression or panic when lightly restrained. If a baby already goes ballistic at this minimal restraint, that does not bode well for its adult behavior during necessary handling. By contrast, a pup that stays limp and calm in a scruff hold demonstrates an inherently trusting and tolerant nature, exactly what we want in our lines.

Reaction to a Human Hand

The Process:

After those handling tests, I place the pup back down in the testing tub. Now I introduce “the big scary hand” into their space. I make a loose fist or hold my hand flat with fingers outstretched and slowly move it near the baby. How does the pup react to an approaching human hand? This tells me about their curiosity and confidence. The boldest pups will approach my hand first, they might scamper right over to sniff my fingers or climb aboard my palm. I love seeing this. It shows the pup sees a human hand as something positive or at least interesting, not a threat. Sometimes a pup doesn’t rush up on their own, but as soon as they see a sibling interact with me, they will come over too, basically “monkey see, monkey do.” That means the pup has social learning ability and some curiosity, even if they weren’t the first. They are following the more confident rat’s lead. This is actually common with slightly shy babies, they gain bravery from their bolder littermates. It’s not a bad thing, as long as they warm up in the end.

A neutral reaction is if the pup just ignores my hand completely, as if it were a piece of furniture. This sometimes happens if they’re more interested in exploring the new bedding or if they simply haven’t connected the hand to a person yet. I will note it, though usually I try a little wiggling of my fingers or offering a scent to get their attention. If they continue to ignore, it suggests a more independent or aloof personality, not fearful, but not super people-focused either.

More telling are the negative reactions: one is if the pup sniffs the hand but then backs off or doesn’t engage beyond that. Sniffing is fine, but if they keep their distance, they might be unsure. A worse sign is if the pup actively runs away from the hand, either darting to the corner or even trying to bury under the bedding to hide. A few pups will panic and bolt as soon as my hand comes near (“panic run away”), which definitely shows fear. In rare cases, a baby might defensively bite at a hand, but at 3 weeks old with minimal prior human interaction, true biting is extremely uncommon (and if it happened, that would be an automatic fail, none of our pups have displayed this interaction in any of our lines). Sometimes the pups will do something quirky like grab the hand and try to wrestle or nibble, if it’s gentle mouthing or climbing, I consider that playful or exploratory (not aggressive).

Why it Matters:

A rat that approaches or interacts with a human hand positively is demonstrating sociability and trust. We breed for rats that actually like people, not just tolerate them. Curious, friendly babies are exactly what pet owners hope for. On the flip side, a rat that consistently hides, ignores, or flees from people will likely be a poor candidate for a pet, especially for a first-time owner or a child. By identifying who the inquisitive, human-oriented pups are at 3 weeks, we know who is on track to be an affectionate pet. And if a pup is completely hand-shy or panicky now, we flag that for monitoring. Sometimes they improve by 5 weeks by learning from their siblings, but if not, that rat might not be placed for adoption. We want to ensure our adopters’ experiences are positive from the start.

Other Notable Behaviors

Sleeping in My Hand:

Believe it or not, some 3-week-old pups are so relaxed they literally curl up and doze off in the middle of being examined. This is a huge green flag, it shows utter trust and calmness. A baby that can fall asleep on a stranger’s hand in a strange place is exceptionally easygoing.

Closing Eyes When Pet:

Often goes hand-in-hand with relaxation. If I stroke a pup’s head and they half-close their eyes or “blep” (stick out their tongue a tiny bit) like they’re in bliss, I note that. It means they are genuinely enjoying the attention.

Grooming Behavior:

Sometimes a confident pup will groom itself or even start licking my hand during the test. A little rat washing its face is usually a sign it’s fairly comfortable (grooming can be a self-soothing behavior). If they lick or “nurse” on my fingers, it’s often an affectionate or comfort-seeking action, they might think my skin tastes salty or reminds them of mom. It’s pretty adorable and usually a good sign they don’t view me as a threat.

Bruxing or Boggling:

Bruxing is when a rat grinds its teeth (usually a sign of contentment or sometimes stress, but in context with body language we can interpret it). Boggling is the funny result of intense bruxing, their eyes vibrate or bulge in and out because of jaw movement, a behavior only seen when rats are very relaxed and happy. It’s a bit early for babies to boggle (that tends to happen in older pups or adults when truly content), but if any are calm enough to brux or boggle during handling, that’s a wonderful note.

Squeaking:

I listen for any squeaks when the pup is touched or picked up. A sudden “eep!” can mean “I’m annoyed or scared.” We really try to avoid breeding lines that squeak in protest to normal handling. Some lines of rats are known to be very vocal complainers, cute in one sense, but it often correlates with low tolerance for being touched or a drama-queen personality. If a baby squeaks every time I pick it up or pet it, I mark that down. It’s something we will watch. Occasional tiny peeps are okay, but repeated loud squeaks are not a trait we favor.

Defensive Postures:

Though rare in young pups, I watch if any baby puffs up fur, thrashes its tail, or shows teeth at me or siblings. That would be an aggressive or fearful display. Not common at 3–4 weeks, but worth noting if it happens.

Dominance or Submission With Siblings:

Since I often test with the litter all in the tub together (handling one at a time but others milling about), I can sometimes observe how they interact. Is one baby bulldozing the others, stealing treats, or constantly climbing on siblings? That might indicate a more dominant pup. Another might consistently cower or stay on the sidelines, a very submissive or shy pup. Neither is inherently bad (rats have natural hierarchies), but extremes on either end are noted. Extremely dominant rats could be more prone to scuffles later, and extremely submissive ones might be easily stressed. Ideally we want well-balanced temperaments that can get along in a group without bullying or being bullied.

Exploration or Perimeter Hugging:

Does the pup boldly toddle around the center of the tub, sniffing new objects (I sometimes put an unfamiliar toy or tunnel in to see if they investigate)? Or do they stick to the edges of the tub and try to hide under bedding? Staying only at the perimeter is a common sign of nervousness (a behavior called thigmotaxis, hugging the walls for safety). A pup that explores everywhere, even the open middle, shows confidence. At 3 weeks, many babies do stay near the sides since it’s their first outing, by 5 weeks we hope to see more adventurousness.

Fear Poop/Pee:

Yes, I check for little accidents. It’s normal for babies to pee or poop in a new place (they have tiny bladders), but excessive pooping the moment they’re picked up can be a sign of fear. We call them fear poops. If I pick up a pup and a few pellets fall out immediately, that tells me the poor thing got scared. A confident rat often won’t relieve itself until it finds a corner or may not at all during a short test. So, if a pup poops on me right when handled, I note that as a symptom of anxiety. Pups that leave a trail of droppings or a puddle whenever frightened are likely high-strung. We will have to see if they relax with maturity or remain nervous.

Biting or Nipping:

Any sign of biting (beyond maybe a gentle nibble out of curiosity) is taken very seriously. A true bite at this age, especially one that breaks skin, is extremely uncommon in a well-bred line, and it would result in a fail. Sometimes babies nibble fingertips as they would a sibling (exploratory mouthing). I differentiate: soft mouthing or “sample nibbles” are okay, but lunging or hard biting is not. If any pup attempts a malicious bite during tests, they would be immediately marked cull (removed from pet placement and breeding consideration) because human-aggressive tendencies are a 100% no-go in our rattery.

Conclusion of the Evaluation

By the end of the 3-week evaluation, I have a pretty detailed picture of each pup’s personality at that moment. I’ll have noted their comfort with handling, their reactions to mild stressors, and any standout traits. On our 3-week form, we also assign an “Overall Rating” to summarize each baby’s performance. The ratings we use at this stage are:

Fail (Cull): The pup showed multiple red flags, such as extreme fear, aggression, or inability to handle basic interactions. Such a pup may be humanely culled or, if not immediately culled, will be very closely monitored for any hope of improvement. (Culling is a difficult topic, but our stance is that adopting out a severely unstable rat does far more harm in the long run, and breeding it is out of the question.)

OK (Monitor for Improvement): The pup had some issues (perhaps very nervous, squirmy, or one concerning behavior) but not so severe as to fail outright. We wouldn’t place this rat for adoption yet; instead we will give it time to improve by the 5-week test. If it doesn’t, it will not be adopted out. Essentially, these are “borderline” pups that get a second chance.

Good (Good Pet): The pup did pretty well. Maybe a little fussy in one part, but generally friendly or at least handled the tests without major fear. This rat is on track to be a fine pet. We will still retest at 5 weeks to confirm, but we anticipate they will be adoptable.

Great (Great Pet / Potential Breeder): The pup was a superstar, relaxed, curious, gentle, and overall exceptional in temperament. These individuals catch our eye as potential breeder holdbacks because we would love to carry forward those genes. If they remain stellar at 5 weeks, we might keep them for our breeding program (depending on how they fit with our genetics and goals). If we don’t need to keep them, they will make wonderful pets, often the ones we would trust even with young children due to their easy-going nature.

After this first round, most pups usually fall into the “Good” or “Great” categories, with a few “OK” that need watching. It is very uncommon for us to label a pup “Fail” at 3 weeks these days, because we have been selectively breeding away from poor temperaments for generations. In the past, if a line produced a pup that utterly panicked or bit, we removed those genetics from our breeding pool. The result is that now we rarely see a total failure. But we do not get complacent. We still test every litter, every baby, because vigilance is how we maintain those high standards. We owe it to our adopters (and our rats) to never assume “oh, they will be fine.” We prove it.

Once the 3-week tests are done, the pups go back to their mom to grow a bit more. Over the next two weeks, we continue weekly mini-evaluations during regular health checks. Each week, as we weigh them and check them over, we note if any pup is becoming overly scared or defensive. Personalities can evolve. A rat that was borderline might blossom with a bit more age, or one that was good could hit a fear period. By keeping an eye weekly, nothing sneaks past us. Usually, however, their trajectories are set by that first test. A confident pup tends to remain so, and a nervous pup, if it is going to improve, shows gradual progress with each handling.

Now, let’s fast-forward to around 5 weeks of age, when it is time for the big final exam!

The 5 Week Old Evaluation

Five weeks old, the babies are now more like teenagers in rat terms. At this age, they’ve been weaned from mom, separated by sex (to prevent any oops litters), and they’re much more coordinated and adventurous. Five weeks is also the age by which we expect to see their true core temperament solidify.

This is our second and final formal temperament test before making decisions about adoptions and breeder holdbacks. We conduct the 5-week test between about 4½ and 5 weeks old. Just like with the first test, we do it in a new environment outside the rattery. In fact, to really challenge their adaptability, we often make the 5-week test solo, one pup at a time, without the comforting presence of their siblings.

Each rat gets a turn in our testing area alone, so we can gauge their individual behavior without any “backup.” This can be an eye-opener, as some pups who were bold with siblings around become a bit cautious alone, and vice versa. I prepare a larger play area or use the same cement tub but with more enrichment for the 5-week-olds. I might add a few novel toys, a small box or tunnel, and a bit of food or treats scattered about. The setting mimics what a new home playpen might be, unfamiliar items, slight noises from the household, and me as the only human present. Then, one by one, I bring each youngster out for their evaluation.

Retesting of Prior Tests

Handling & Petting:

I want to see if they maintain the same level of relaxation they showed at 3 weeks, or if they now have a tendency to resist more as their strength and independence have grown. For example, a rat that was "mostly relaxed, but squirms a little" at 3 weeks and now fully relaxes is showing a positive trajectory in trust and comfort with human touch.

Any pup that is still freezing in fear, fighting touch, or attempting wild jumps at 5 weeks is likely not going to make a stable pet. It’s rare, but if it happens, that rat will be marked as a Fail for adoption. Conversely, those that are cuddly and calm now earn top marks. We love seeing a rat who just flops contentedly in our hands at 5 weeks, as if to say “I’m ready for a lifetime of snuggles!” (It’s worth noting: we still have not heavily socialized them prior to this 5-week test. Other than routine care, we don’t flood them with attention between 3 and 5 weeks. This is so the behaviors we see now are truly ingrained, not just because we trained them. Their genetic temperament is on full display. Only after passing this 5-week exam do they start intensive socialization, which I’ll describe soon.)

Flip Test:

I gently roll them onto their back and watch for cues like stiffening, wiggling, or mouth opening. This isn’t about dominance; it is about seeing if they can accept gentle restraint without panic. A fully relaxed rat is ideal, but I also look for those who may wiggle initially and then settle. That adaptability is often a good predictor of how they will cope with unexpected handling at the vet or in a child’s hands.

Most critically, if any rat now at 5 weeks opens its mouth threateningly, shrieks, or shows terror when flipped, that’s a huge problem. Occasionally a hormonal spurt can make a young male less tolerant, but at 5 weeks they’re usually too young for hormones to fully kick in, so such a reaction would likely be temperament-based. This would be a Fail trait. Thankfully, it’s exceedingly uncommon in our litters by this age, because the extremely fearful ones (if there were any) wouldn’t have made it this far.

Dominance Test:

The pinned flip test is a follow-up where I use my fingers to hold them lightly in place. Some will squirm and then submit, which can still be a good sign if they give up quickly. Rats that continue to resist, squeak loudly, or appear distressed are noted carefully. While not an automatic disqualification, consistent resistance across multiple tests is a red flag for a pet home that wants a calm, low-stress companion.

Scruffing or Vertical Hold:

At 5 weeks we tweak the scruff test slightly. They’re larger now, so instead of a full dangle by the scruff, I often do a “vertical hold,” supporting their butt in one hand while holding them upright by placing a hand around their chest (almost like how you’d hold a small dog upright). Alternatively, I scruff them briefly just to see. Many 5-week-olds will still kick a bit initially (that “whoa I’m off the ground” reflex), then they chill out. I also take note if any actually start out calm but then begin to squirm after a moment (“relaxes then struggles”), that can simply mean they got bored or wanted to go explore, not necessarily fear. We differentiate it: an exploratory squirm (the rat’s whiskers are forward, not panicked, maybe trying to climb onto my arm) is different from a frantic squirm (ears back, tail whipping, trying to get free).

True resistance is when the rat is having none of it, body thrashing, maybe a foot pushing against my hand, or turning to try to grab me to get me to release. If I see that, and especially if it doesn’t ease up quickly, it’s a strike against their score. By this age, they should at least tolerate a brief restraint if their temperament is solid.

Hand Approaching:

This time I am watching more for initiative. Will they come up to me on their own? Do they need to see another rat do it first? Do they ignore me altogether? A bold approacher might do well in an active, busy home, while a more reserved rat might be better suited to a quiet, patient household.

At 5 weeks, many will outright climb into my hand looking for treats or a lift. They’ve learned humans can be treat dispensers by now (we often introduce a few hand-fed treats around 4–5 weeks, but sparingly until the test to not influence it too much). If a rat joyfully sniffs and hops on my hand, that’s recorded as “touches/climbs on it,” an excellent sign of trust. If one completely ignores me, I might have to get their attention; often truly ignoring doesn’t happen unless they’re hyper-focused on something else. Still, a somewhat aloof rat might explore the bin and pay me no mind, could just be independent. I’ll note if they show no interest in people.

If a rat runs away or avoids my hand at 5 weeks, that’s more concerning than at 3 weeks, because by now they’ve had two weeks to become accustomed to normal household activity and brief handling. A panicky retreat or frantic avoidance of me signals lingering fear that hasn’t resolved. That rat would not be a top candidate for adoption, especially not to a novice owner. Thankfully, most have improved by this point, even the shy ones usually will approach for a treat or out of curiosity eventually, especially in a safe test space. Those that still hide from the hand get an “hides” or “panics” mark and likely a lower overall score.

Additional Testing Points

At 5 weeks, we retest many of the same additional traits we looked for at 3 weeks, such as relaxation during handling, grooming behaviors, bruxing or boggling, vocalizations, defensive or dominant postures, exploration versus perimeter hugging, fear poops, and any signs of biting or nipping, to see if those early tendencies have stayed the same, improved, or worsened. In addition to these repeated checks, we add several new observations to capture the rats’ developing personalities, confidence, and independence. By now, they are more coordinated, bolder, and socially aware, which allows us to evaluate how they interact one-on-one with humans, play with toys, respond to new situations alone, and reveal whether they are more people-focused or self-reliant.

Reaction to Play

The Process:

During the 5-week test, we assess how the rat engages in play and interacts in a slightly larger space. I might gently tickle the rat’s back, similar to how we play with well-socialized older rats, almost like a game of chase or tag. I may also let them scamper off my lap and then pat the ground or wiggle a toy to see if they return. We note different possible behaviors. A rat that comes back right away is very people-oriented, as if saying “Nope, I’d rather be with you!” One that comes back after some time may explore first, then respond when called, showing independence with a willingness to interact. If they investigate by chasing my hand or pouncing on a toy, they are engaged and curious. If they ignore my attempts to play, they might simply not be interested at the moment or not understand the game. A rat that runs away or hides in response to play shows discomfort or low confidence, while one that freezes in fear, sitting immobile with wide eyes, is clearly overwhelmed.

Why it Matters:

This part of the test helps determine how sociable and resilient each rat is. Playful, curious rats that return to me tend to adapt well to busy, interactive homes and may be a great fit for families seeking an outgoing pet. Rats that avoid interaction or hide might be better suited to quieter homes with patient owners who can give them time to open up. A rat that is very play-avoidant would not be placed with small children, as it may become stressed by high-energy handling. Matching a rat’s energy level and confidence to the right home ensures the best outcome for both the rat and the adopter.

Reaction to a Loud Noise

The Process:

At 5 weeks, we introduce a sudden, unexpected sound to assess startle response and recovery. I warn any human family members nearby that a loud noise is coming, then I create it by clapping sharply, jingling keys, or dropping a hardcover book flat on the floor. Almost all rats will startle slightly, which is normal. I then watch what happens next. An ideal response is a brief freeze followed by curiosity, such as coming over to investigate the noise or looking to me for cues. Some bold pups might even popcorn in surprise, then immediately resume exploring or sniff around to check the source. Another excellent reaction is minimal response beyond an ear twitch, which indicates a very steady temperament. A moderate response might involve jumping, hiding briefly, then peeking out and recovering. A more fearful reaction is running to hide and staying cowered for a long period or freezing in place without moving. A surprised squeak means the rat was highly startled. The most extreme reaction, which we almost never see in our lines, is a panicked frenzy with frantic darting or attempts to escape the bin that do not subside quickly.

Why it Matters:

Life brings many unexpected sounds, from clanging pans and vacuum cleaners to thunder or children playing. We want rats to handle these surprises with as much composure as possible. A rat that recovers quickly or becomes curious after a startle is well-suited for an active home. A rat that cannot recover and remains fearful may become stressed in a noisy household. Identifying sound-sensitive pups allows us to guide adopters toward a suitable match or avoid placing the rat in a chaotic environment. Selective breeding has greatly reduced noise sensitivity in our lines, and after passing this test, rats are regularly exposed to normal household sounds so they learn to take them in stride. The 5-week noise test serves as a baseline measurement of their natural nervous system resilience.

Reaction to Offered Treats

The Process:

During the solo 5-week test, each pup is offered a small treat by hand, such as a dab of baby food on a spoon, a Cheerio, or a piece of banana. The ideal reaction is to accept the treat without hesitation and eat it comfortably in front of me, showing both trust and food motivation. Some pups will take the treat but run to a corner to eat it, which is normal prey-animal behavior and still a positive sign. A cautious rat might sniff but refuse the treat, indicating unease or low food motivation, which can make bonding and training slower. An undesirable reaction is mistaking my finger for the treat and nipping. While a gentle nip is usually an accident, repeated instances are noted as “nibbles fingers instead of treat” and suggest overexcitement or reactivity, which requires caution around children. If a pup shows no interest in either the treat or my hand, it is recorded, as it can signal nervousness or low engagement. During this test, I also gently pet or approach the rat while it eats to check for food aggression. If a pup stiffens, growls, lunges, or bites when approached during eating, it is considered a serious red flag and that rat would not be placed for adoption.

Why it Matters:

Taking food from a person is a simple but effective trust check. Rats that happily and gently accept treats are often easy to bond with and train, as they associate humans with positive experiences. A rat that refuses a treat may need more time to develop trust, while one that grabs too eagerly could unintentionally bite, making them less suited for homes with small children. The food aggression check ensures the rat is comfortable with human contact during eating, which is important for safety and for a good pet-owner relationship. By identifying trust, food motivation, and manners at this stage, we can match each pup to the right type of home and avoid placing potentially problematic rats in situations that could lead to stress or injury.

Solo Exploration in a New Zone

The Process:

A major part of the 5-week test involves observing how a rat behaves alone in an unfamiliar environment. I place the pup in the testing area, such as a safe playpen or tub, with a variety of new objects. I watch to see whether the rat interacts with these items, like sniffing or climbing through a tunnel. Confident rats typically investigate most or all objects out of curiosity. I also pay attention to body language, noting whether their movement is fluid and relaxed or jerky and hesitant. Fluid movement suggests comfort, while quick darting motions can indicate nervousness.

I look for any signs of panic, such as frantic dashing or leaping attempts to escape the area. While rare in our lines, this behavior is a clear indicator of distress. Freezing or huddling in one spot for the duration of the test also signals discomfort. Another key observation is whether the rat ventures into the open center of the area or sticks to the perimeters, similar to the scientific open-field test for anxiety. Confident rats will roam freely, including across open spaces, while more anxious ones cling to the edges.

If there is a hideout available, I note whether the rat uses it briefly or stays hidden the entire time. Persistent hiding points to fear, while brief sheltering is less concerning. Some rats will spend time testing the boundaries of the enclosure, trying to find a way out. This can indicate adventurousness or a desire to return to familiar surroundings. I also see whether the rat will eat from the environment, as a relaxed rat will usually find a piece of scattered food and nibble it. Refusal to eat often reflects higher stress levels.

Self-grooming is another behavior I track. A quick wash during the session generally shows the rat feels safe enough to focus on something other than potential “threats”. Over-grooming or a total lack of grooming may point to anxiety. I also note if the rat approaches me during the test, standing on hind legs or interacting as if seeking comfort or connection.

If a rat seems more nervous than usual, I sometimes introduce a littermate to see if their confidence improves. This is recorded as “performs better with a friend.” Rats that explore more freely with a companion may be follower types, relying on braver friends for reassurance. We avoid pairing two highly follower-type rats together, ensuring each pair has at least one confident individual to help the shyer one adapt.

Why it Matters:

This test provides a detailed look at a rat’s environmental confidence and adaptability. Rats that explore, engage with objects, and appear comfortable on their own tend to adjust more easily when moving to a new home. These rats are often independent and brave, which means they are less likely to experience prolonged stress during transitions. Conversely, rats that panic, hide, or remain frozen may need extra support, such as pairing with a calm, confident companion or being placed with an experienced owner who can help them gradually build trust. Understanding these tendencies allows us to make better adoption matches and ensure each rat is set up for success in their new environment.

Conclusion of the Evaluation

After going through all these observations, we give each rat an Overall Score/Disposition rating on our 5-week form. This final rating directly impacts what happens next for that rat. Our 5-week scoring rubric is a bit more detailed than the 3-week one:

Fail (Cull): Sadly, if a rat scores this low, it means it failed to meet our temperament standard. This would be a rat that perhaps still exhibits intense fear, overly defensive behaviours, or other serious issues even after both tests. Such a rat will not be placed for adoption. In practice, this is almost always a cull from our breeding program as well, to ensure those traits do not carry on. We might humanely euthanize if the issues are severe and likely to result in suffering or unsafe behavior, or in some cases we might keep the rat in a sanctuary capacity if we believe it can live comfortably but just is not pet material. (Again, this is extremely rare due to our selective breeding, most “bad” temperaments have been long bred out.)

OK (Not Great for Kids/First-timers): This category is for a rat that is adoptable, but with reservations. Maybe they are a bit skittish or hyper and did not quite make “good” status. We would not want to send this rat to a home with young children or someone who has never had rats before, because it might require patience or experience to bring out its best. These are rats we might adopt out to an experienced rat owner who will respect the rat’s boundaries and help bring it out of it's shell, or we might hold them longer for extra socialization to see if they improve. They are not culls because they are not aggressive or utterly terrified, but they are not our top-tier easy pets either. We will always be transparent with adopters if a rat is in this category, explaining that it might be a bit more work.

Good (Good Pet): This is your solid, all-around good pet. The rat passed all basic tests, maybe it is still a tad shy in a new environment, or wiggles when held, but nothing concerning. We consider these perfectly adoptable to any average pet home. With normal love and attention, “Good” rats become wonderful companions. Many rats in this range simply have moderate energy or took a little longer to warm up, but they like people and have no aggressive or extreme fearful tendencies. They would be fine for a first-time owner, under our guidance.

Great (Excellent Pet, Even for Kids): A rat that scores 4 is exceptional in temperament, the kind that is so friendly and bomb-proof that we would trust them with gentle children, therapy pet situations, or anyone. They are usually the ones that actively seek human interaction, recover instantly from surprises, and handle all manner of touching with ease. These “great” rats often become the adopters’ favorites and sometimes we get feedback like “I cannot believe how sweet and calm he is!” They are a joy to place in homes because we know they will likely adapt immediately and just be little angels.

Breeder Holdback (Temperament): Rats scoring 5 (and above) on our scale are beyond great, they are top of the top in terms of temperament. A “5” for us specifically denotes a rat we are strongly considering keeping for our breeding program due to its stellar personality. This rat is not only a great pet candidate but has some quality (health, temperament, etc.) that we want to perpetuate. If we mark a baby as a 5, typically we will not list it for adoption until we decide whether we need it for breeding. It might be reserved as a “temperament holdback.” Only the sweetest, most people-oriented, gentle rats get this distinction. Often these are the ones that were rated “Great” at 3 weeks and continued to impress at 5 weeks. Sometimes we don’t have a need for more breeders in a particular line and will just offer these rats for adoption along with their siblings.

Breeder Holdback (Genetics): This is a special category where a rat might be kept primarily for its genetic traits (like a rare color, markings, or other lineage value) and it has a decent temperament (at least “Good”). We would never keep a nasty-tempered rat just for a color, so any holdback must have acceptable temperament, but a “6” might indicate the rat is good (not extraordinary) in personality, yet carries an important trait we need in our breeding program. We will hold it back to improve our lines genetically. For example, if we need a healthy outcross or a particular coat type in our program, and that baby is okay with handling though not the cuddliest, we might still keep it as a breeder in a project line. They would score 6 in that case, “holdback for genetics.” Adopters likely will not see many 6’s because those rats are not usually posted for adoption (they stay with us).

Breeder Holdback (Genetics & Temperament): The jackpot! A rat that has everything, amazing temperament and desirable genetics, would score a 7. These are very rare and valuable to us. If we are lucky enough to get a baby that is both one of the friendliest we have ever seen and has, for example, a unique coat or comes from a line we want to strengthen, that baby is almost certainly staying here to become a future parent in our rattery. Essentially, a 7 is “please clone this rat, thank you.” They are the ones we hope will pass on both their sweet nature and their physical traits to many generations.

Most of our adoptable rats end up being in the 3–4 range (Good or Great). The 5–7 range are typically our holdbacks. As for 1–2, as mentioned, those are either not adopted out at all (failures) or only under special circumstances (OK but needs experienced home).

By the end of the 5-week testing, we now have a clear profile of each rat. Only the babies who pass both evaluations (3-week and 5-week) are ultimately put up for adoption. If a rat failed at 3 weeks, it was already removed from the pool (unless we gave it a second chance and it improved by 5 weeks). This double filter means that by the time you see a rat listed as available from us, that little one has proven twice over that it has a stable, people-friendly temperament.

Why Two Tests Are Better Than One

By comparing results from the 3-week and 5-week tests, I get a fuller picture of each rat’s temperament. Sometimes a pup who was shy at 3 weeks becomes confident by 5 weeks after seeing the world a bit more. Other times, a rat who seemed bold early on shows signs of pushiness or overstimulation later. This is why we never rely on just one evaluation. We want to confirm that positive traits hold steady over time and that any concerns are not just a one-day fluke.

Only rats who pass both evaluations are made available for adoption or considered for breeding. This means that when an adopter meets our available rats, they can trust that these animals are already screened for stable, people-friendly temperaments.

Between Testing and Adoption

Once the 5-week evaluations are complete, we take a moment to celebrate, the hard part is done, and now the fun begins! The pups that have passed their tests are given their official names (somehow naming feels like a reward, an acknowledgment that they are joining the ranks of “real” pet rats) and we prepare to list them for adoption. But we do not simply throw them on a website and call it a day. The next 1 to 2 weeks before they go home are crucial for social development. Up until now, we have somewhat held back on excessive handling, but after 5 weeks we intentionally ramp up the socialization big-time. The reason we wait is to avoid masking as discussed, but once they have shown us who they are, we want to polish those innate temperaments into the best they can be. Here is what happens in the interim between testing and adoption:

Integration with the Colony:

We move the weaned pups into our general population cages by around 5 to 6 weeks old. This means they get to live with and learn from some of our older rats (often we have “nanny” females or gentle older males that we introduce them to, depending on sexes). The older rats become their mentors in a sense. They teach the babies “how to be a proper rat,” everything from litter box etiquette (yes, our adult rats help train the young ones by example in using litter trays) to how to politely groom and play without hurting, and even how to beg for treats nicely from humans. The mixed-age interaction is invaluable.

For instance, a slightly timid baby often gains confidence seeing an older rat stroll up to us for scritches. They learn that humans are not scary because their new adult friend is not scared. It is a bit like putting a shy kid in a class with friendly older kids, they tend to come out of their shell faster. By the time they go home, our pups have experience meeting unfamiliar rats and maintaining good social behavior, which means they integrate more easily into new groups and adapt to multi-rat dynamics better.

Household Experience:

We start exposing them to normal household life. This includes common noises like the vacuum cleaner running nearby, TV or music playing, the clanking of dishes in the kitchen, etc. Now that we know they are temperamentally sound, we want to ensure they are familiar with these sounds so they will not be spooked in their future homes.

We even invite different people (for example, my spouse or a friend) to handle them gently, so the babies learn that all humans can be friends, not just me. This extra step helps prevent a phenomenon where a rat is only comfortable with its breeder and is shy with new people. By giving them positive interactions with multiple voices and scents, we broaden their comfort zone.

Daily Handling & Play:

Now is when we indulge in all the cuddles we have been holding back! The babies get handled every single day, multiple times a day, by everyone in the household. We make it fun, short sessions of lap time, being carried around for a few minutes, gentle tickling and wrestling with a hand (rats do play-wrestle with humans if you tickle them around the neck, it builds trust and mimics rat roughhousing). We also let them ride on shoulders (with caution), sit in hoodie pockets, and explore on the couch or bed under supervision. These experiences teach them that being with humans equals good times. We keep sessions positive and not too long, respecting if a baby seems overstimulated (though by 6 to 7 weeks, most are just loving the attention).

New Toys & Enrichment:

We introduce new toys, textures, and challenges to them daily. One day they might get crinkly paper to play in, the next a hanging bird toy to tug, another day a little obstacle course. This not only keeps their minds stimulated, but it ensures that by adoption time, they are used to encountering new things regularly. A rat that has been acclimated to novelty is less likely to freak out when their new owner gives them a strange toy or if they see a new room. They learn to approach new objects with curiosity instead of fear.

Gentle Training:

During this week or two, we often start teaching small polite behaviors. For example, we reinforce that hands bring treats, so they learn to come when called or at least come to an open hand. We might start litter training officially (most pick it up quickly after watching adults). We sometimes teach them to accept being in a bonding pouch (a little pouch worn by a person) or to come to the cage door for attention or even on a leash. Some super smart ones even start learning their names if we use them consistently. By no means are they fully trained in a week, but think of it as us giving them “kindergarten” education before sending them off.

Continued Monitoring:

We do not stop observing temperament during this phase. It is informal, but I keep an eye out for any rat that suddenly seems off, maybe one is getting overly bossy as hormones kick in, or one got startled by the vacuum and is taking a while to settle. If anything concerning pops up now, we address it. For example, if a young male started showing unusually aggressive play or nipping at others (which could hint at early hormonal behaviors), we might pull him for further evaluation. However, it is extremely rare to see a drastic change at this point. In fact, almost all the results of our testing hold true into adulthood.

The few changes we do see are usually positive: often a somewhat shy baby will blossom into a more confident teen once it is in the perfect home with the perfect cage-mate dynamic. Because we matched it appropriately, it gains courage. It is gratifying to hear updates like, “That timid girl I adopted is now the bold explorer of the duo!” Usually, any evolution in personality is 99% for the better, given the solid foundation we have laid. It is very rare for a rat that passed our tests to later develop aggression or extreme fear out of nowhere. (If that ever occurred, say a rat became aggressive at sexual maturity, we would work with the owner on solutions like neutering or, if it were a kept breeder, we would not breed that rat. Thus far, our careful selection has kept such surprises to a minimum.)

Matching Rats to the Right Homes

Throughout the testing process, we are also thinking about which rat might suit which home based on notes given in adoption applications and conversations with adopters. We keep notes on who is more energetic, who is more laid-back, who loves kids (some of our rats seem to especially enjoy small humans’ antics), and who might prefer a calm environment. For example:

If a family with young children is adopting, we lean towards the most patient, gentle rats for them (those “Great, adoptable to kids” scorers). These are rats that will not mind being manhandled a bit and will not nip even if a child’s hand is clumsy. They are often the ones that come to the front asking to be picked up and seem to enjoy being carried.

If an experienced adult adopter wants a pair to take hiking or traveling (yes, some people do leash-train rats or bring them on adventures), we might suggest some of our boldest, most curious boys or girls, the ones who scored high in exploration and barely flinched at loud noises. These rats are usually game for anything and will not be stressed by changing environments.

For someone who wants cuddle bugs to chill on the couch, we know to pick the calmer, super snuggly individuals. Perhaps a rat that was more inclined to sit and groom in the test zone rather than race around, or the one that fell asleep in my hand, those will likely be lap rats.

If a home is adopting an existing solitary rat a friend, we will consider that current rat’s personality and pick a complementary youngster. For instance, if the resident rat is older and mellow, we might give them a gentle but moderately confident friend (not hyperactive that could annoy the senior, but not so timid that the older one’s territory scares it).

We also ensure that the pairs of rats we send home have good dynamics with each other. We often pair a slightly shy rat with a more confident sibling, so the shy one has a buddy to model bravery. Or we avoid putting two strong-willed alpha types together. Our notes from testing guide these pairings. The goal is that each pair or group has a nice balance of personalities that get along and enrich each other.

In short, by the time our rats are posted for adoption, they are not just randomly up for grabs, they are essentially pre-screened and matched to the kinds of homes where we believe they will thrive. We often discuss with adopters what they are looking for (cuddly vs. playful, etc.) and use our testing insights to recommend the best fits. This level of matchmaking is something we are very proud of; it leads to happier pets and happier owners.

The Importance of Temperament Testing

You might wonder, reading all this, is all of this really necessary? Couldn’t one just handle babies a lot and assume they will be fine pets? Or pick the “friendly acting” ones at 5 weeks and ignore the rest? In our experience and philosophy, doing formal temperament testing is extremely important for anyone breeding rats responsibly. It is our way of continuously improving the species’ pet quality and ensuring no family ends up with a biter or a fearful animal that they cannot enjoy. The extra effort we put in early saves so much potential trouble later.

Consider the alternative: pet store rats or breeder rats from lines with no testing. They might seem tame when young (especially if hand-raised), but without screening, you have no guarantee what behaviors might emerge as they mature or face stress. Sadly, that is how some owners end up with aggressive males at 6 months old, or a rat that cowers in the corner for a year, scenarios that often lead to those rats being surrendered or isolated. By contrast, our system greatly reduces those surprises. Since we have started this rigorous protocol, instances of serious behavior problems in our adoptees have dropped to almost zero.

It is about responsibility: if we bring new lives into the world, we owe it to them to give them the best start and only send them to homes if we are confident they will be great pets. Furthermore, genetic temperament is something you can only improve by selection. By removing the worst-tempered individuals from the gene pool and breeding only the sweetest, we are contributing to future generations of even better pet rats. It is long-term thinking. Each round of testing informs our breeding choices: the rats that score highest become our next moms and dads. Over time, this selective breeding for temperament has led to noticeable consistency. Our litters now are uniformly friendlier and more people-loving than what we started with years ago. It is incredibly rewarding to see that progress, and it is directly thanks to the data we gather from these tests.

Some might say our methods are a bit over the top, after all, these are tiny creatures with a relatively short lifespan and we are talking about “evaluations” like they are in school. But we balance it with compassion. The tests are designed not to traumatize but to gently provoke natural responses. We do not force the babies into terror; we give them novel situations and see what they do. And because we truly care about each rat’s well-being, any who do not handle the tests well are spared from being thrust into a home where they would be miserable. Instead, those rare ones are handled within the safety of our rattery, with full understanding of their needs. It may live out life here or be humanely euthanized if its quality of life is poor. These are tough decisions, but they underscore how seriously we take temperament. A good temperament is not just a luxury, it is essential for a pet to have a good life and for the pet owner to have a good experience.

Before I conclude, I want to address a common question: Does temperament testing guarantee a rat will never bite or never be fearful later? The honest answer is no, individual animals can always surprise you, but our process greatly minimizes the chance of bad behavior emerging. We cannot control every aspect of life, if a rat experiences trauma or severe illness, it might react in uncharacteristic ways. But because we have bred for solid nerves, even in hard times our rats tend to cope better.

And importantly, we stand by our rats. If an adopter ever has trouble, such as a rat not adjusting or acting out, we are here to help. We will provide advice, training tips, or if needed, we will take the rat back and either work with it or re-evaluate the situation. We never want anyone to feel stuck with a pet that is not right for them, and we never want a rat to be in a home where it is not welcomed. Part of responsible breeding is having that safety net.

A Final Word

In summary, temperament testing is the cornerstone of our rattery. It is a lot of work, yes, but it is work that pays off every time we send home a pair of baby rats and hear later how wonderfully they are doing. Our goal is to produce not just pretty rats, but ideal pets that will bring joy for their entire lives. By carefully observing and selecting for the right traits at 3 weeks and 5 weeks, and then nurturing those pups with socialization, we are confident that any rat you adopt from us will be among the friendliest and sweetest you can find. So the next time you see our litter announcement and wonder why only certain rats are available (and others are not listed), remember all the behind-the-scenes steps that led to those posted babies. Each one has been through our “rat rookie training camp,” passed with flying colors, and is now eagerly waiting to bring some lucky person a lot of love. We do this because we truly love rats and want to set every single one of them up for success, as cuddly pets in your home and as ambassadors of how amazing pet rats can be when bred and raised with care.

Thank you for reading this in-depth journey through our temperament testing process. We hope it gives you confidence in our rats and perhaps a new appreciation for the little individuals they are. When you adopt from us, you are not just getting a rat; you are getting a companion whose personality has been thoughtfully observed and encouraged from the very start. And that, to us, makes all the effort completely worth it.